“Nel nostro rapporto raccogliamo le informazioni fornite da molti

soggetti diversi” spiega Alessandro Trigila, responsabile per l’Ispra

del progetto Iffi, monitoraggio dei fenomeni franosi “quindi da Re-

gioni e Provincie autonome per quel che riguarda le frane e dalle

Autorità di bacino per quel che riguarda l’erosione, in pratica le al-

luvioni. Naturalmente, abbiamo dovuto omogeneizzare tutti questi

dati, visto che ciascuno li ha forniti secondo i propri criteri mentre

noi abbiamo dovuto riportare tutto a criteri comuni. Quello che vie-

ne definito, appunto, mosaicatura”.

Tra le tante indicazioni, sicuramente uno stretto rapporto con le at-

tività agricole che possono, per un verso, aggravare i rischi e le con-

seguenze degli eventi climatici sul territorio, per altro possono co-

stituire il miglior presidio per la sua difesa.

“L’agricoltore tende a modellare il terreno per facilitare le sue atti-

vità di semina e di raccolta” spiega Trigila “quindi di primo acchito

vorrebbe ridurre i dislivelli e facilitare le operazioni meccanizzate.

Per esempio, si sono abbandonati progressivamente i terrazzamenti,

che richiedono una manutenzione soprattutto per i muri a secco.

Ma questo tipo di interventi ha un effetto deleterio, favorendo i fe-

nomeni sia franosi che erosivi. E le conseguenze tornano a danno

della stessa agricoltura. Allora si è passati alle colture ad alto va-

lore aggiunto, come le olive taggiasche, che sono tipiche di terreni

più irregolari e per questo richiedono un ricorso maggiore alla ma-

nodopera. Ma trattandosi di colture pregiate, il maggior costo è sta-

to ampiamente recuperato con il maggior prezzo finale”.

Di “buone pratiche agricole” si occupano anche i Consorzi di boni-

fica, in tutto 150, che a loro volta effettuano interventi di manu-

tenzione ordinaria ogni anno per una spesa complessiva di circa

600 milioni di euro, ma presentano anche un piano straordinario

di prevenzione, che è sempre rimasto un libro dei sogni. L’ultimo

presentato, che si riferisce al 2015, prevede interventi per 8,5 mi-

liardi. In passato, solo alcuni interventi di quelli suggeriti dall’Anbi

(www.anbi.it)l’associazione dei consorzi di bonifica, sono stati ef-

fettivamente realizzati dallo Stato.

“Il bilancio dei nostri Consorzi, ovvero i 600 milioni all’anno che

spendiamo per la manutenzione ordinaria, è costituito dai contri-

buti dei nostri associati, ovvero tutti coloro che posseggono una

proprietà nel perimetro del consorzio” spiega il presidente dell’An-

bi, Francesco Vincenzi “mentre il piano straordinario che mettiamo

a punto partendo dalla conoscenza del territorio, riguarda interventi

che necessariamente dovrebbero essere presi in carico dallo Sta-

to. Noi, comunque, facciamo anche un’attività di formazione per

suggerire agli agricoltori come si può realizzare un’attività proficua

e, al tempo stesso, intervenire sulla difesa del suolo. Posso fare

un esempio: basta effettuare l’aratura in senso trasversale, anzi-

ché longitudinale rispetto alla pendenza, per contribuire al conteni-

mento dell’acqua nel terreno. Naturalmente, queste cautele valgo-

ing a private association – has a peer-to-peer dialogue with pub-

lic institutions. Other initiatives are promoted by regions and mu-

nicipalities in the name of local autonomy, such as surveys and

plans of maintenance interventions, clashing with limited finan-

cial resources and inefficiency of public bodies. Most of the times

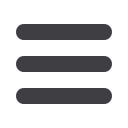

these are emergency plans following natural disasters such as

landslides or floods, then reported globally. The work by Ispra

consists, to a large extent, in preparing a homogeneous map by

collecting several documents, in an attempt to assess the de-

mands of the entire country. This operation is called, in techni-

cal jargon, “mosaicking”.

“In our report we collect information supplied by many different

bodies”, explains Alessandro Trigila, manager at Ispra of the Iffi

project for the monitoring of landslides, “by regions and au-

tonomous provinces on landslides and by Basin Authorities on

erosion and floods. Of course, we have to collect all the figures

and then standardise them, since each authority provide them

according to their own criteria. This process is in fact called mo-

saicking”. “There is definitely a close relationship with agricul-

tural activities which may, on the one hand, increase risks and

consequences of climate events on the territory and on the oth-

er hand be the best defense for its protection”.

“A farmer tends to shape the land to facilitate its sowing and

harvesting”, explains Trigila, “and so at first glance he would

rather reduce height differences of soil and facilitate mecha-

nized operations. For example, there has been a gradual aban-

donment of terraces, which require specific maintenance, with

a special regard to dry stone walls. However, this type of inter-

vention has a harmful effect, as it favours both landslides and

the process of erosion. As a consequence, High-value specialty

crops, such as Taggiasca olives from Liguria – typical of the most

uneven lands and requiring greater care and more intense use

of labor – are often preferred. These are profitable crops, the

higher costs of which have been largely recovered thanks to a

higher final price”.

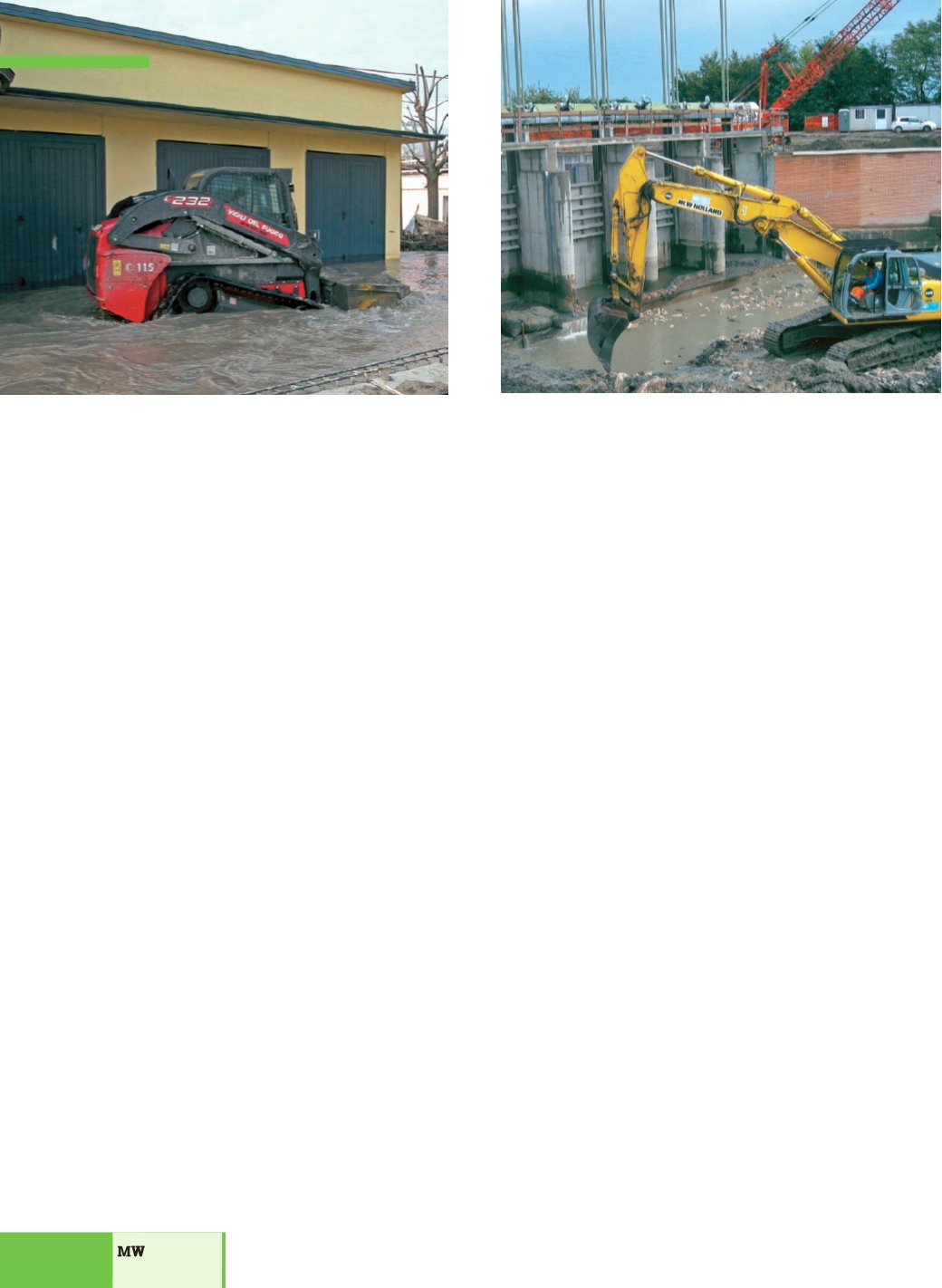

The 150 Land Reclamation Consortia are involved in the issue of

“good agricultural practices”, providing yearly maintenance inter-

ventions for a total amount of 600 million euro and publishing an

extra plan of prevention, that has never been implemented. Last

plan of 2015 included interventions for 8.5 billion euro. In the past,

only a part of the maintenance interventions suggested by Anbi (As-

sociation of Land Reclamation Consortia –

www.anbi.it)was car-

ried out by the State.

“The budget of our Consortia, equal to 600 million a year, spent

for ordinary maintenance, is in fact represented by membership

fees, payed by the owners of a property within the consortium

perimeter”, explains the president of Anbi Francesco Vincenzi,

66

n. 7-9/2016

TEMI